The History of Sport in Public Schools

The growing prominence of sport

In the early part of the 19th Century, sport and games were of very little interest to the headmasters of the leading public schools. Involvement was sparing, other than intervening when necessary to prevent isolated incidents of violence and brutality between boys or to halt the actions of boys rampaging around land neighbouring the schools.

However, as the century progressed there was a growing acceptance amongst the new educators to see value in games and the characteristics its involvement could help develop. Indeed, the Clarendon Commission of 1864 commended the leading public schools, of which Winchester was one, for “their love of healthy sports and exercise.” It was felt, despite the severe punishments administered through the fagging system, that games taught Englishmen “to govern others and to control themselves.” Such leadership skills were what Thomas Arnold, as Head of Rugby School (1828-1942), identified as fundamental to the development of discipline and morality amongst gentlemen and became essential qualities to foster through the prefect system.

By the middle of the century, games had been formally embraced by headmasters to such an extent that they began to employ masters purely for their ability in games. The emergence of sport as part of the formal school provision in public schools was rapid and within the space of twenty years, schools had gone from having occasional ‘hare and hounds’ runs to full sports meetings. In 1845, Eton’s annual steeplechase commenced, followed by those at Cheltenham and Harrow in 1853, Rugby in 1856 and Winchester in 1857.

Courage and endurance were also essential physical traits which could be developed through games and football was certainly something which actively promoted such virtues. Through more formal instruction, a process of civilising took place, whereby the scrum, or its idiosyncratic derivatives such as the “Hot” at Winchester, became an institution of the public schools.

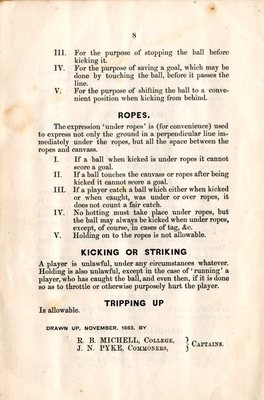

The first record of football being played at Winchester was in 1825 with 25 players on each side, goals were 27 yards away, and were simply a line cut in the earth, there being no crossbar (though no goal could be kicked above five yards high). The game was extremely physical and as dribbling was forbidden one of the main objectives of the game was to charge down the opponent’s shots, believed to have been a very painful business. Indeed, according to other sources, football at Winchester was known to be particularly violent with boys regularly taken to hospital with broken bones. Interestingly, such ailments didn’t seem to deter their fellow squad-mates who waited to take the place of the injured. This could well be the reason why we still have a five-man substitute bench in XV’s today. It was probably the sheer physical pain of playing which prevented its adoption at University but Winchester’s football game was probably the model for the field game introduced at Eton.

It was from the memories of two authors (C. Wordsworth and A. Leach) who suggested the rules of the Winchester game were not printed until 1863 and that initially Winchester’s football was badly organised until at least 1839, with matches only being arranged the evening before. Nevertheless, by all accounts the prefects were regimentally efficient in their treatment of juniors “insisting that they stand, often shivering, for more than an hour merely to kick the ball back if it went out of play”.

Football at the various public schools remained very insular, with boys retaining the distinctive aspects of their game, typified by their often unique and peculiar rules. Unsurprisingly, such games did not lend themselves to contact with external teams or other schools and while it would be false to suggest that footballers at these schools remained distanced from outsiders, very little interaction occurred. This situation slowly began to change towards the middle of the nineteenth century as more open-minded headmasters saw the need to challenge the blinkered elitism of only playing amongst themselves, although there was a still division of sorts. Until the 1840s Harrow only recognised Eton, Winchester, Westminster and Charterhouse as public schools and while there is no evidence of snobbery affecting the interactions between public schools on the football field, it is by no means impossible that it was a factor in determining the selection of suitable opponents.

Contact between public schools on the football field appears to have been first suggested in 1827, when Wykehamists challenged Eton to a match on Egham racecourse. Eton rejected the challenge because Winchester had stipulated that both sides should ‘dress in high gaiters and mud boots’ (Eton College Magazine vii (5 November 1832).

The real catalyst for a more frequent programme of inter-school fixtures was the formalisation of a codified set of rules. A meeting of representatives from the major public schools met at Cambridge University in 1848 with the stated aim of standardising the games played between them. For several years the various institutions had played each other by sharing the rules of their respective version of football and playing one half with one set of rules and then swapping for the second half. The Cambridge Rules were duly noted and formed the code that was adopted by the football teams of Eton, Harrow, Rugby, Shrewsbury and Winchester. This also ensured that when the students eventually arrived at Cambridge, they all played with the same rules.

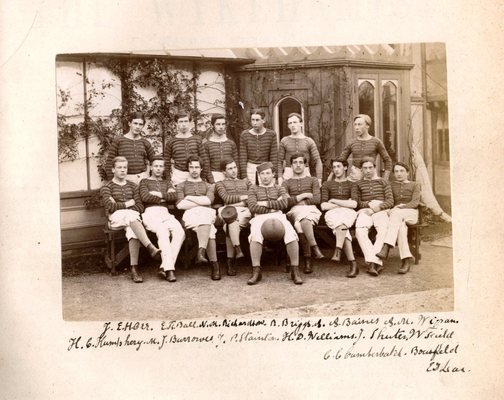

The Gentleman Amateur

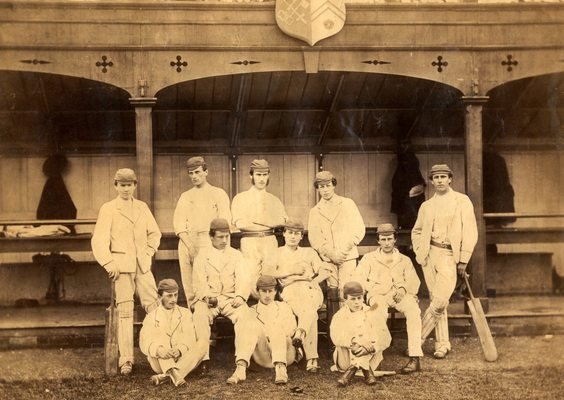

Although the development of football has garnered most of the attention so far, save for the odd mention of steeplechase, sports such as cricket, rowing, tennis and athletics were also essential components of the school sports programme during the nineteenth century. The driving philosophy behind the promotion of these sports was the fact they were seen as a vehicle for instilling values such as camaraderie and co-operation. Hand-in-hand with these virtues was the emphasis on creating the archetypal gentleman amateur who played sport not only to the written rules but also to the nobler concept of the spirit of the game. Moreover, the embodiment of the gentleman amateur was someone who could play several games extremely well without giving the impression of strain or the need to indulge in additional physical training.

This ideal has been greatly romanticised over the years and for such an individual to be adept at playing so many games so well he undoubtedly needed to belong to the wealthy upper classes. Nevertheless, sporting prowess across several disciplines became the mark of the classic public schoolboy and one Wykehamist Olympian, George Robertson, certainly embodied this when he claimed medals at the first modern Olympiad in Athens (1896) in discus, shot put and doubles tennis!

The sporting all-rounder who could display the combination of athletic vigour and true sportsmanship became a sought after figure for diplomatic and civil service roles at the turn of the twentieth century across the Empire. According to Holt (1989), the Sudan Political Service recruited entrants from 1899 through an interview process primarily based upon recommendations from trusted dons in Oxford and Cambridge. In fact, of 393 entrants to the administrative grade, 71 had full representative sporting honours from Oxford or Cambridge, and many more were highly proficient sportsmen drawn from the older established public schools, Eton, Rugby, Winchester and Marlborough.

The skills and attributes one can develop through sport are still fundamental reasons behind the extensive school extra-curricular programme within schools such as Winchester in the twenty-first century. Characteristics such as leadership, discipline, team-work, cooperation, resilience and determination are as highly valued now by employers as they were in the late 19th century and so sport’s prominent role within the public schools will continue to be significant for years to come.

References:

Harvey, A. (2005) Football: The First Hundred Years: the Untold Story, Routledge Holt, R. (1989) Sport & The British: A Modern History, Oxford University Press Johnson, B. www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Association-Football-or-Soccer Mangan, J. (1992) The Cultural Bond: Sport, Empire, Society (ed), Frank Cass

Cited references

Leach. A. (1899) History of Winchester College, Duckworth Sherman, M. (1904) Football, Oakley & Co Wordsworth, C. (1891) Annals of my Early Life, Longmans

Head back to stories

Head back to stories