Crucifixus

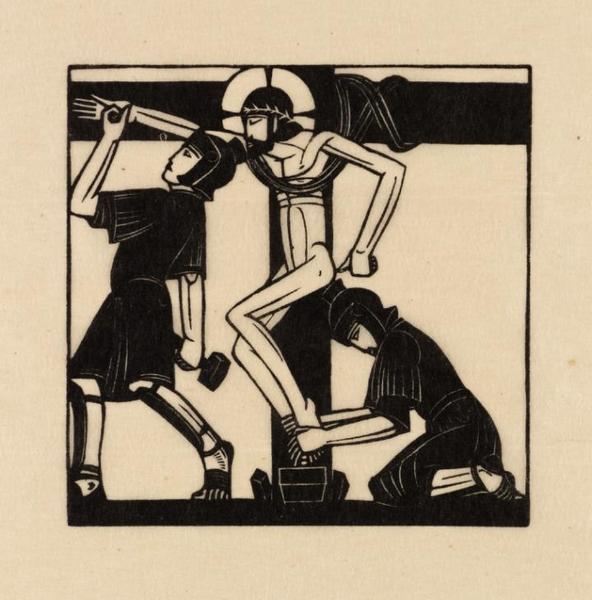

This morning, we were due to gather in the Cathedral for our Passiontide Service. The theme this year was Stations of the Cross. The eleventh station – Christ nailed to the cross – is vividly depicted below by the English engraver Eric Gill. At this point in the service, the Chapel Choir would have sung Antonio Lotti’s Crucifixus.

Born in Venice, Lotti spent most of his life in the service of the church, with his most notable appointment being Maestro di Cappella at St Mark’s Basilica in the mid-18th century. However, it was his time at Dresden as court composer that produced Crucifixus, his most famous work.

The words describing Christ’s crucifixion and death, from the Nicene Creed, have led to some extraordinary outpourings from composers over the centuries. JS Bach, in his Mass in B Minor, depicts Christ’s suffering in continuous descending chromatic lines, with the voices plummeting to the depths of their vocal range and then hushed to a silence. In the Missa Solemnis, Beethoven also sends his music ever downward, faltering and eventually grinding to a complete halt.

Lotti’s approach to these profound words differs, especially at the very beginning. Written for 8 voices, each part enters bar by bar starting with the lowest basses, piling up the musical texture with suspensions (musical crunches in the harmony) and creating a piercing intensity by the time the highest voice enters.

One of my favourite recordings of this magical work was performed in Saint-Chapelle, Paris and sung by the British vocal ensemble Tenebrae, conducted by Nigel Short.

In the world’s current turbulent state, music can and will transport people in relative isolation to a better place, helping them to cope. For me, Lotti’s Crucifixus is the perfect addition to your play list for moments of solace and peace.

Head back to stories

Head back to stories