Medieval Stained Glass at Winchester College

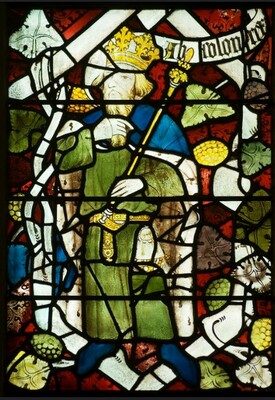

The College has medieval glass from three separate programmes in its collection: a mid-thirteenth century scene from the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris (now in Treasury), the late fourteenth-century glass of the College Chapel, and an early sixteenth-century window in the south wall of Thurbern’s Chantry.

A new booklet written by Eleanor Townsend and Sarah Griffin, Medieval Glass at Winchester College, looks at how and why each programme of glass was commissioned, their content, and their history since the Middle Ages. Created across a period of significant artistic change, they demonstrate the development of stained glass production techniques and the Gothic style from the mid-thirteenth to sixteenth centuries.

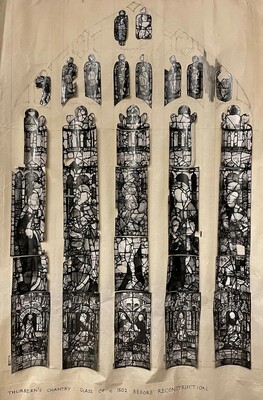

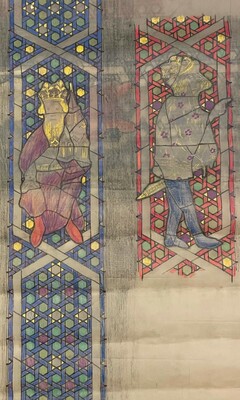

Details from each programme of stained glass. Centre and right images © Gordon Plumb

Winchester’s glass in the twentieth century

The focus of Medieval Glass at Winchester College is what the glass can tell its observers about art in the Middle Ages, yet this is just one aspect of its rich history. Each programme has since been extracted and moved between buildings, their appearance inevitably altered in the process. Extensive research on the original arrangement of the glass of the College’s chapel and chantries has been undertaken in the past century and the College is fortunate to have considerable archival materials that record their study.

The project to uncover the history of the College’s stained glass began with attempts, in the early twentieth century, to track down the fourteenth-century glass of the Chapel’s east window that had been removed in 1821 (for more on this story, see Tim Gidding’s recent Trusty Servant article). The art historian and Old Wykehamist Kenneth Clark, when purchasing some of the pieces for the College in 1949, wrote, ‘I have never written a cheque with greater emotion’. Their return raised questions as to where they would be installed, leading to a re-organisation of the glass in Fromond’s and Thurbern’s Chantries. The reorganisation of the glass was led initially by John Harvey, consultant architect of the College 1947–64.

One of Harvey’s tasks was to reconstruct an early sixteenth-century window, which had been partially cut down when moved from Thurbern’s to Fromond’s Chantry around 1772. In planning the reassembly, he drew intricate, to-scale drawings of the windows, and made collages using photographs of his arrangement of the glass pieces. Seeing these multi-media documents from a time when cameras were not so readily available, I felt grateful for my tablet, which had been my own way of understanding the original placement of parts of the fourteenth-century glass (see page 9 of the booklet).

The windows—large, centuries-old puzzles taken apart and pieced back together multiple times—will never again show a completely reliable image of their medieval appearance. Yet evidence of their extraction, dispersal, as well as their meticulous reconstruction, provide a rich source of the changing attitudes to medieval art over time.

Head back to stories

Head back to stories