A Plague on all the Houses: An Epidemiological History of Winchester

I am under strict instructions from the experts not to begin this article with the simplistic assertion that Winchester College was founded to train replacement priests for those killed in the Black Death. That outbreak of bubonic plague in 1348-9, which killed somewhere between a third and half of England’s population, did indeed take a terrible toll on Winchester – no surprise when the entry-point for the plague into England was nearby Melcombe, today part of Weymouth. The area which Wykehamists call Hills Valley is also known as Plague Pits Valley, because mass graves were dug there once the city’s cemeteries were full. And clerics were hit hardest of all: 49% of beneficed clergy in the diocese died (and 44% of monks), making it the worst-affected diocese in the country. William of Wykeham’s predecessor as bishop, William Edington, had to fill 300 parish vacancies in 1349, as opposed to the normal number of about 12. However, when Wykeham founded the school over three decades later in 1382, that particular recruitment crisis was long in the past.

Nevertheless, whilst there was a recruitment crisis in Wykeham’s episcopate, it was not so much that plague-induced gaps needing filling, but that normal gaps were no longer being filled. The numbers coming forward for ordination had drastically reduced since the Black Death. In the two decades before that epidemic it was not unusual for over 100 men to be ordained at just one of the four annual ceremonies in the Winchester diocese. In 1362, when Wykeham himself was ordained, only 19 men were ordained in the whole year; in 1371, a meagre 33. Some of this decline can be attributed directly to plague: the Black Death was just the first of 31 outbreaks in late medieval England, and a smaller population would produce proportionally fewer priests. But the bigger effect was indirect: the population decline expanded the opportunities for ambitious young men, tempting potential priests into rival careers. A freer market in land allowed smaller operators to build up larger holdings. Renewal of the wars against the French and Scots offered the rewards of military success. And an enormous expansion of legal activity created a need for many more lawyers. Those who in the previous generation might have opted for ordination now had better opportunities available elsewhere.

So Wykeham did want more priests. But he also wanted more educated priests, and greater opportunities for poor pupils to be those priests – pupils from a similar background to himself, the son of a Hampshire yeoman. It is these latter two concerns which are most prominent in Wykeham’s Foundation Charter of 1382. In fact, no mention at all is made of the Black Death or any other plague in Winchester’s Charter or Statutes. The New College Charter (1379) does mention that the number of clerks had been affected by ‘epidemics and general pestilences, wars and disasters, rising food prices and other misfortunes’, but this is more a generic catalogue of the repeated plural ills of the 14th century than a specific reference to the disaster of 1348. The Winchester Charter is much more focused on educational philanthropy: he wished to benefit the ‘poor and needy’, ‘the many poor scholars intent on school studies suffering from want of money and poverty’. He wanted them to be able to ‘become more amply and freely proficient in the faculty and science of grammar’.

In searching for Wykeham’s motives for founding the school, then, we can simply take his professed motives at face-value: he wanted to give an education to boys who may not have been able to afford one so that the parishioners of the diocese could be served by a competent priest.

Wykeham did lay down detailed instructions for keeping his new school free of sickness. Any scholars who fell ill could to stay in College as normal for a month (in practice confined to their chambers); should the illness persist, they should be removed to ‘a decent place outside the College’ with an allowance for three months; any still ill at the end of that would ‘cease to be scholars’ and be replaced within eight days to keep the numbers at their foundational level. The danger of water-borne diseases breaking out was lessened by the on-site Brewery, which continued to supply a daily alcohol-purified beverage to the pupils until 1916.

When an epidemic did strike the medieval school, the whole community was simply sent home. In fact, such summer absences were so common in the early 16th century that one school historian mistook them for a regular holiday (pupils at this time were only granted a vacation at Whitsuntide). In 1543, when the Great Death spread to Winchester from London, the boys were away for 18 weeks – no opportunities for remote learning via Skype and OneNote back then!

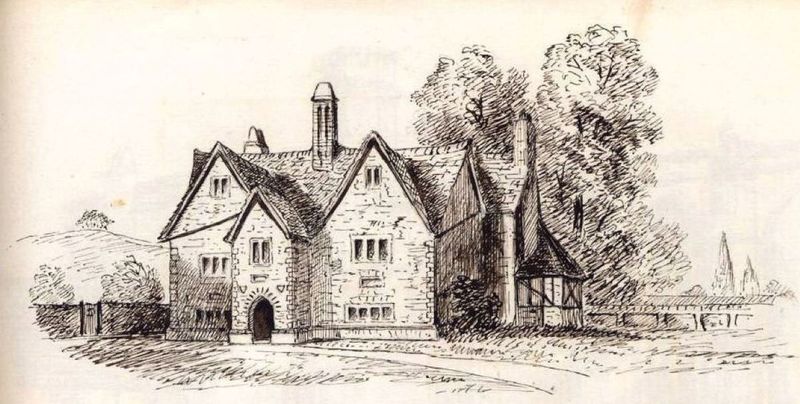

To avoid a repetition of such extended absences, the school designated Moundsmere, a manor south of Basingstoke acquired in 1544 in a land-swap with Henry VIII, as a refuge to which the whole community could be evacuated during future epidemics. A barn was built for their reception with money given to the College by Mary Tudor and Philip of Spain on the occasion of their wedding in Winchester. The tenant of the manor remained bound by lease to set aside rooms for evacuation up until 1887. The barn, alas, burnt down in 1915, but can be seen on the 1771 map of Moundsmere.

Map of the manor of Moundsmere, William Hampton, 1771, watercolour

The early 17th century saw several outbreaks of plague. The 1603 outbreak caused the Law Courts to be moved from London to Winchester; James I turned the school out of its buildings so that his judges and sergeants could be housed – consequently, no pupil had the chance to witness the trial of Sir Walter Raleigh in the Great Hall. In 1625 the worst outbreak since the Black Death hit Winchester, causing the principal and wealthiest inhabitants of the city to flee.

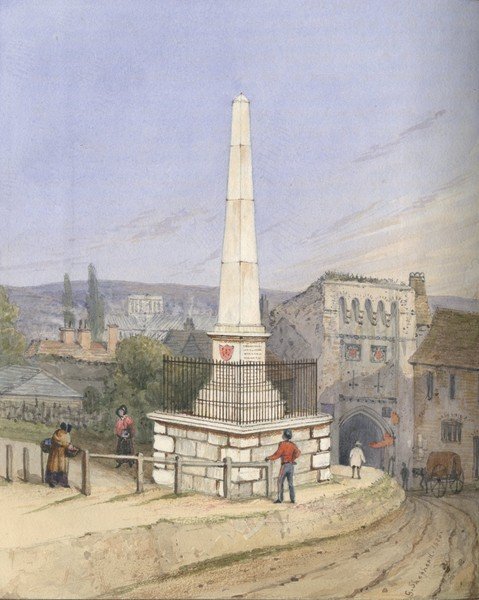

The 1665-6 Great Plague of London, recorded most famously by Samuel Pepys but also by OW William Emes, also reached Winchester. Its eventual passing is commemorated by the 1759 obelisk near the West Gate, on the site just outside the city walls where remaining citizens purchased essentials from traders unwilling to enter the city; supposedly they left the money in bowls of vinegar. There was a mass exodus into countryside; the pupils of Winchester College were evacuated again for the month of Pentecost, this time to a farm-house rented in Crawley, with £2 paid to allow the boys to play in an adjoining meadow. There is a theory that it was pupils quarantined there who wrote ‘Domum’, longing for the homes where they would usually be spending their Whitsun holidays.

Plague Monument, G. Shepherd, 1826, watercolour

The practice of leaving sick scholars in their chambers to infect their peers for a month was ended by the construction of Sick House in 1656-7 by Warden John Harris, who is commemorated in the poignant inscription to the right of the door: ‘The boys’ prayer for the builder. May Jehovah guard, cherish and sustain his heart and limbs as he lies on his last bed sickness’; he died in 1658. The building was expanded in 1775 by John Taylor, Fellow.

Sick House (now called Bethesda), 1656

The Victorian reformers continued to make improvements. A typhoid epidemic in 1874 prompted the school to connect itself into the city’s new water system in 1879. And the construction in 1886 of Sanatorium, with its two wards, isolated Fever Wing and two operating theatres, hugely expanded medical capacity: in 1918 one ward was used during the Christmas holidays for 40 or 50 wounded soldiers overflowing from the Red Cross hospitals.

That year brings us to the Spanish ’Flu. Many comparisons have been drawn between our current COVID-19 crisis and that epidemic, which killed about 228,000 in the UK and an estimated 50 million worldwide. It seems that Winchester got off very lightly. Headmaster Monty Rendall wrote, ‘In Cloister Time (during July) the influenza epidemic which was prevalent throughout England attacked Winchester. Quite a third of the School suffered from it; but the cases were not severe and did not last long.’

The last hundred years have generally been much healthier. There was an outbreak of polio in 1947, and an epidemic of ’flu in 1990 caused the school to break up three days early for Christmas. The most recent epidemic to strike the school was H1N1 in 2009 – the so-called swine ’flu. At one stage, around a third of pupils were off lessons. Once dons starting succumbing, eager boys began to speculate about the possibility of repeating 1990’s early start to the holidays. But they were met with a firm answer: ‘We can cope without the dons. As long as the cooks are healthy, the school can carry on.’

Head back to stories

Head back to stories